Most cloud programmes don’t fail loudly; they silt up. A team gets its first isolated workspace, someone hand-crafts network segments and firewall rules, access policies are cloned “just this once”, and six months later those one-offs are the norm. Costs blur, environments drift, and every new team re-discovers the same base setup—usually by asking Ops for exceptions. What’s missing isn’t a bigger change board; it’s a landing zone that treats the foundation as a product.

By “landing zone”, I don’t mean a slide deck or a giant IaC module. I mean a repeatable contract: when a team asks for an environment, they get the same paved road every time; clear hierarchy and isolation, identity and access patterns, baseline networking, encrypted storage, central logging, budgets, and policy as code. Guardrails replace gatekeepers. The experience is self-service, not ticket-driven; variance is deliberate and controlled, not improvised.

Done well, a landing zone aligns four concerns that usually fight each other: identity, network, security, and cost, and makes them defaults rather than afterthoughts. This article stays hyperscaler-agnostic on purpose. The landing-zone idea isn’t a vendor feature, it’s a set of transferable patterns you can reapply on any platform. We’ll cover the essentials that don’t change: how to structure isolation and hierarchy, shape identity and access, lay down baseline networking, make security and compliance run in the path as policy, and keep cost visible by default. Then we’ll turn that into a paved road (scaffolds + guardrails), define a minimum viable landing zone you can stand up in weeks, sketch a migration path from a single overgrown workspace, and finish with the metrics that tell you it’s working. If you swap out the logo, the patterns hold, that’s the point.

What a landing zone really is

As described in the introduction, a landing zone is a repeatable contract, not a slide deck or a pile of scripts. Here’s what that feels like in practice.

A concrete scenario: a new payments team needs a non-production environment today. They sign in with short-lived credentials, run a “create service” starter, and a fresh repository appears with CI/CD, infrastructure modules, and observability already wired. The first pipeline run provisions an isolated workspace under the right hierarchy (kept separate from production), applies baseline network segments and egress rules, turns on encryption by default, connects logs/metrics/traces to central sinks, and stamps required labels/tags so budgets and ownership are visible. Access is granted by roles, not ad-hoc users; secrets come from a managed store; policy as code enforces the guardrails in the path. A second pipeline deploys the service with a safe rollout (flags/canary and automatic rollback available), registers routes and DNS through a standard integration, and publishes default dashboards and alerts.

No tickets. No side direct messages. No “who owns DNS?” The team ships features; the platform proves safety.

Two ingredients make that reliability possible:

Starter kits, not blank repos.

Instead of handing teams a wiki and wishing them luck, the platform offers opinionated templates for both services and environments. A single command (or pipeline) gives you a repository with CI/CD, infrastructure modules, sensible defaults for runtime configuration, and the basics of observability (SLOs, alerts) already wired. The result is consistency without ceremony: teams start shipping features, not scaffolding.Guardrails in the path, not approvals at the gate.

Controls run as code where changes flow; admission policies, dependency/image rules, required labels/tags, encryption checks, egress limits, provenance and attestation are in the build. These guardrails prevent drift and unsafe changes automatically, and they produce evidence your auditors can trust. When an exception is needed, it’s explicit, time-boxed, and auditable; no permanent snowflakes.

Treat the landing zone as a product, not a project. It has versions; upgrades arrive with migration playbooks and a compatibility window. The platform team watches conformance and drift, listens to where delivery slows (onboarding, networking, identity, policy noise), and tunes the paved road accordingly. Evidence replaces meetings: conformance reports, attestations, and rollout metrics live in the pipeline, not in spreadsheets.

You’ll know it’s working when the conversation shifts from “who can approve this change?” to “what proof shows it’s safe, and how fast can we recover if we’re wrong?”.

In short, the landing zone is a versioned, measurable contract. Starter kits give teams speed; guardrails keep that speed safe; the pipeline carries the proof.

The reference shape

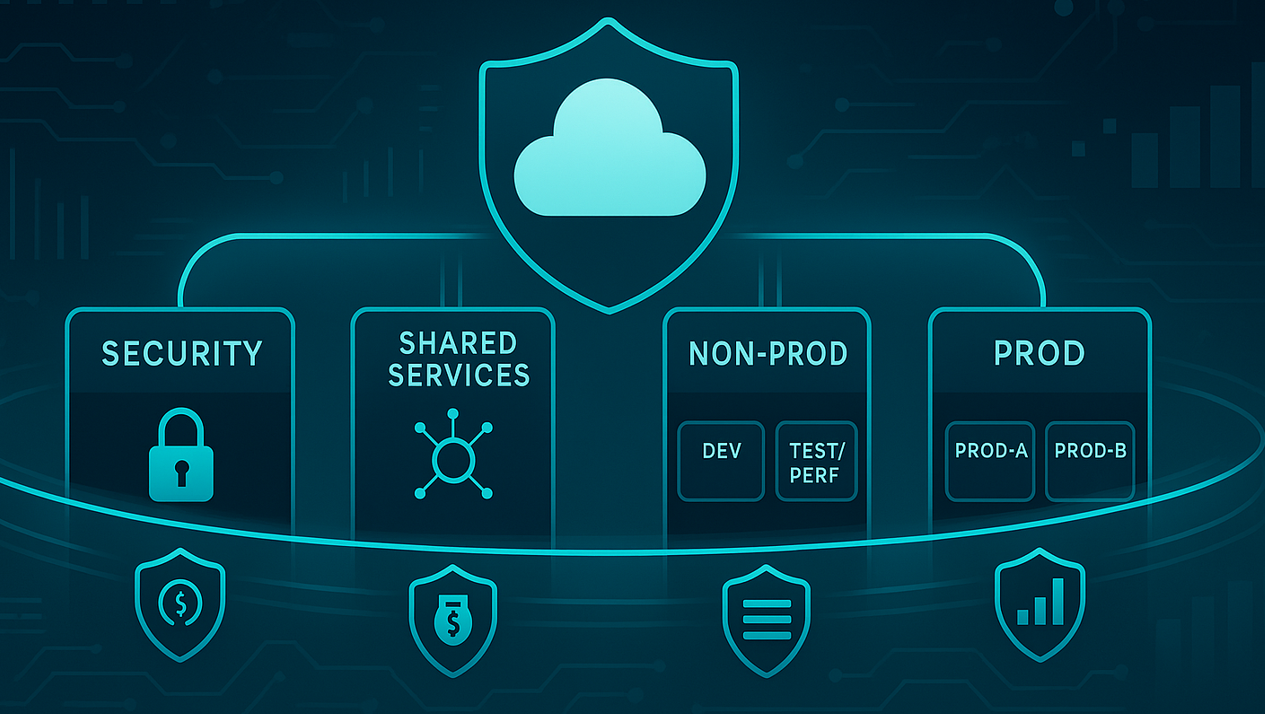

Start at the top and work your way down. Picture an organisation root with a few sibling spaces beneath it, each with a clear job. Production and Non-Production sit side by side so you can set different policies without inventing exceptions. Security stands apart to run detection, audit, and key management. Shared Services hosts the things everyone relies on: identity, CI/CD, artifact storage, the network hub, and observability. If you need a Sandbox/Research area, give it looser quotas but strong isolation and auto-expiry so it doesn’t become a landfill.

With the shape in place, identity comes first in practice. People and workloads use single sign-on, get short-lived credentials, and inherit roles defined by the platform (engineer, operator, analyst). Human access is read-mostly by default; when elevated rights are truly needed, a break-glass path exists that’s time-boxed and auditable. Workloads authenticate without long-lived secrets wherever the platform allows; think federated identities rather than copy-pasted keys.

Networking is the next lever. A hub-and-spoke (or cloud-WAN-style) layout keeps shared egress, name resolution, and private service endpoints in one place, while each team’s workspace remains a well-bounded spoke. Service-to-service access is expressed as policy, not scattered firewall rules. Crucially, connectivity is created by pipelines as code, so you can review it, roll it back, and explain it six months later.

Your security baseline should feel boring in the best way. Encryption is on by default, in flight and at rest. Logs, metrics, and traces land in central sinks without anyone wiring them by hand. Backups exist with tested retention. Posture checks and drift detection run continuously, not just before an audit. Supply-chain hygiene is part of the build: artifacts are signed, dependencies checked against policy, and build provenance recorded. When someone truly needs an exception, it’s explicit and it is time-bound.

On cost and ownership, you don’t chase spreadsheets, you rely on data. Every resource carries required labels/tags (owner, environment, product, cost centre, etc.), budgets and alerts are set per team, and dashboards report unit economics (cost per request/job/user) instead of vague totals. Guardrails prevent unlabelled resources and block the handful of configurations that can surprise your bill.

Paved road = scaffolds + policies

A landing zone only feels fast when the thing you start from and the rules you run under ship as one. Think of the paved road as a versioned contract with two halves that move together.

Scaffolds (golden starters)

A good starter doesn’t hand you a blank repo; it drops you into a shaped one. The repository comes with a sane layout, branch protection, and CODEOWNERS so responsibility is obvious and reviews attach to the right people. The included CI/CD flow builds, tests, scans, and packages once, then promotes the same artifact through environments. That single chain shrinks lead time and gives you an auditable trail without a change board.

From the first push, the service lands inside the guardrails. Infrastructure modules stamp out identity and roles, network segmentation, storage classes, DNS/ingress and sensible quotas, so isolation, routing, and encryption aren’t follow-up tickets. Configuration and secrets are wired to the platform store with short-lived credentials; no keys in repos, no one-off patterns. Observability is already there: logs, metrics, and traces flow to central sinks, default dashboards render, and an SLO template links the service to reliability goals from day one.

Releases are designed to be reversible. Feature flags, canary or blue/green rollouts, health checks, and auto-rollback are built in, so you rely on technical safety instead of permission meetings. The software supply chain is treated as a first-class concern: SBOMs are generated, artifacts/images are signed, vulnerability thresholds are enforced, and build provenance is recorded making “what exactly shipped?” a query, not a war room. Every resource is created with ownership and cost tags, which keeps spend attributable and dashboards trustworthy. A lightweight set of runbooks and service docs: health endpoints, on-call notes, escalation paths means incidents build capability rather than chaos.

Finally, the scaffold carries policy as tests. Conformance checks for tagging, encryption, IAM scope, and egress run in CI, catching drift before it reaches production. A single bootstrap command (or pipeline) provisions the workspace and performs the first deploy, turning “time-to-first-value” into hours. The effect is cumulative: teams start compliant, pipelines emit the evidence, and the platform can version and evolve the contract without asking every team to reinvent the basics. In a landing zone, that’s the point, the safe path is the easy path, by default.

Policies (controls in the path)

Guardrails only earn their keep when they live where changes flow. In a working landing zone, policy is code that runs in pipelines and control planes, not a checklist at the end. The effect is immediate: unsafe patterns never make it past the build or admission layer, and safe patterns carry their own proof.

Practically, this means risky mutations are blocked at source. Storage won’t go public by accident; encryption is required rather than recommended; resources without ownership and cost labels simply don’t create; and network egress is scoped by default instead of “allow any”. The same discipline applies to the software you ship: images and artifacts are signed, SBOMs are generated automatically, dependency policies are evaluated with clear thresholds, and builds produce provenance so you can answer “what exactly is running?” without a meeting.

At runtime, platforms enforce admission policies: workloads that don’t meet baseline constraints: resource limits, security context, ingress/egress rules, image provenance are rejected before they land. Secrets are backed by managed cryptography and short-lived credentials so long-lived keys don’t leak into repos or environments. Every control leaves a trail: attestations, conformance reports, and audit records are machine-readable and bundled with the artifacts they certify.

Two details keep this humane. First, exceptions exist but are explicit, time-boxed, and auditable; an escape hatch, not a side door. Second, policies are versioned alongside the scaffolds they protect, with migration notes and a conformance score surfaced in CI, so teams can upgrade deliberately rather than discover breakage late. The net result is less ceremony and more confidence: lower change-failure rate and time-to-restore, without stretching lead time with approvals theatre.

With guardrails in-path, you replace permission with proof: safe-by-default for 95% of changes, exceptions explicit and time-boxed.

Keep them one thing

When scaffolds and policies drift, the organisation slows—pipelines start failing for “policy reasons” or worse, controls are relaxed to keep velocity. Treat the paved road as a single, versioned artifact:

- Version the contract:

paved-road vX.Y. - Ship updates with migration playbooks and a compatibility window.

- Track a conformance score per service/workspace and surface it in the pipeline.

If a control doesn’t reduce change-failure rate or time-to-restore, it’s latency, not a landing-zone requirement. The paved road earns its keep by making the safe path the fast path.

The minimum viable landing zone (MVLZ)

You don’t need a committee or a quarter to “finish the foundation.” You need a first slice that works end-to-end and proves the path. The MVLZ is that slice: a small set of decisions that make the safe path the easy path on day one, and that you can extend without rewrites.

What must exist on day one (thin but real)

- Hierarchy & isolation: an org root with peer spaces for Non-Production and Production, plus separate Security and Platform. Team workspaces live under Non-Prod/Prod, no nesting Prod beneath anything else.

- Identity & access: single sign-on; role-based, short-lived credentials for people and workloads; auditable, time-boxed break-glass.

- Network baseline: segmented address space; private service endpoints; central egress and name resolution; default-deny egress with explicit allowances.

- Observability by default: logs/metrics/traces flow to central sinks; a starter dashboard and alert route ship with the template; an SLO stub exists even if targets are rough.

- Security defaults: encryption in flight/at rest; image/artifact scanning and provenance; dependency policy with sensible gates; secrets managed—not in repos.

- Cost & ownership: required labels (owner, env, product, cost centre) enforced; budgets and alerts per team/product; a simple spend dashboard people trust.

- One starter template: a “hello-service” scaffold that builds/tests/scans, provisions an isolated workspace, deploys with canary/rollback, emits telemetry, and tags everything.

How to ship it in weeks (not quarters)

- Name the contract. Write down the MVLZ scope and the defaults (identity, network, security, observability, cost). Version it:

paved-road v0.1. - Stand up the shape. Create the root and the four sibling spaces (Security, Platform, Non-Prod, Prod). Apply stricter policy to Prod; keep Non-Prod permissive but safe.

- Wire identity. Enable SSO, define platform roles (engineer/operator/analyst, etc.), issue short-lived credentials; set up workload identity/federation where available.

- Lay the network. Central egress and DNS; private service endpoints; default-deny egress with a small allowlist (artifact registry, metrics, identity).

- Publish the starter. A single command (or pipeline) that creates a repo, attaches CI/CD, provisions an isolated workspace, deploys, and registers telemetry.

- Put policy in the path. Add policy checks to CI and admission (tagging, encryption, provenance, egress rules); make exceptions explicit and expiring.

- Prove it with a real service. Move one non-critical service onto the paved road; exercise canary and auto-rollback; capture evidence artifacts.

- Show the numbers. Time-to-first-deploy, lead time, CFR, MTTR, and conformance score; make them visible in the pipeline, not a slide.

Definition of done (MVLZ)

Done isn’t a slide, it’s a working path a new team can use today. Use these checks to prove your first slice is real, safe, and repeatable:

- A new team can self-serve an environment and deploy in less than a day using the starter.

- Lead time measured in hours, not weeks, for that service.

- Change-failure rate < 5% with canary/auto-rollback available.

- Time to restore < 1 hour, rehearsed once (game day).

- 0 unlabelled resources; all logs/metrics/traces present by default.

- Evidence (attestations, conformance reports) produced automatically.

What comes next (iterate, don’t boil the ocean)

Expand in small, deliberate steps: define data boundaries and cross-account/project access patterns; add cross-region DR and prove backups with verification SLOs; set rotation SLOs for secrets and track key provenance; extend your starters to cover stateful and batch/ML workloads; and tighten spend with unit-economics guardrails (cost per request/job/user). The MVLZ isn’t “minimal” because it’s thin—it’s minimal because every piece earns its keep. Start small, make it work, measure it, then evolve via versioned upgrades, not another queue.

Common traps (and how to avoid them)

Even well-intentioned landing zones can drift into bureaucracy or stall under their own complexity. The failure modes aren’t usually technical, they are system design: policies that block reality, templates that age quietly, a platform run as a queue instead of a product, and “safety” that’s really latency. Use this section as a field guide: each trap names the smell, explains why it appears, and shows how to replace permission with proof and ceremony with flow. The goal isn’t a perfect rulebook; it’s a foundation that stays fast, safe, and adaptable as your estate grows.

Policies with no escape hatch

It’s easy to write a policy that forbids everything risky; it’s harder to design for reality. When there’s no safe “break-glass” path, teams invent side doors—long-lived keys, shadow repos, one-off pipelines, and your neat posture collapses. Fix it by making exceptions first-class: time-boxed elevation with automatic expiry, recorded justification, and alerts to owners. Tie exceptions to SLOs and error budgets (e.g., stricter when budgets are burned). You’ll keep velocity without normalising bypasses.

Golden templates that silently rot

Starters age the moment they ship. Six months later, new services use v4 while half the fleet runs v2 with different IAM, network, and observability wiring. Now your platform isn’t a platform; it’s archaeology. Treat templates like a product: semantic versioning, change logs, compatibility windows, and automated upgrade paths (codemods or migration playbooks). Run a nightly “golden canary” that exercises the latest starter end-to-end and publish a conformance score per service so drift is visible and fixable.

One landing zone to rule them all

A single monolithic foundation usually means the worst of both worlds: over-permissive for regulated data and over-restrictive for everything else. Instead, keep a thin base contract (identity, isolation, encryption, telemetry, tagging) and add layers (overlays) for special cases: regulated workloads, data-perimeter constraints, cross-region DR, high-throughput batch. Overlays are versioned modules, not forks; teams select capabilities, not bespoke snowflakes.

Approval theatre instead of technical safety

If your controls don’t move change-failure rate or time-to-restore, they’re latency. Long queues feel safe but just batch risk. Replace permission with proof: progressive delivery (canary/blue-green), health checks with auto-halt/auto-rollback, pre-prod parity you can trust, and policy-as-code in the pipeline. Keep the human review where it matters (design, risk acceptance), not where machines are better (repetitive conformance checks).

Platform run as a ticket queue, not a product

When “open a ticket” is the primary interface, your capacity becomes the bottleneck. Run the landing zone like any customer-facing product: a roadmap, SLAs, usage analytics, and research with your “customers” (teams). Measure time-to-first-deploy, lead time, DX friction (onboarding time, template adoption) and prioritise the backlog accordingly. Documentation is part of the product; so are self-service wizards and error messages that explain how to fix, not just what failed.

Policy sprawl and alert fatigue

Hundreds of rules with low signal-to-noise train teams to ignore warnings. Curate a small, high-signal policy set with severity tiers (blocker/warn/info). Every rule must have an owner, a rationale, and a test. Expire temporary rules. Review policy effectiveness quarterly against DORA/SLOs; delete or downgrade rules that don’t reduce CFR or MTTR. Less, but sharper, creates trust, and compliance improves.

The common theme: design for flow with evidence. Keep the base small and reliable, let capability grow through versioned overlays, and measure outcomes. When the safe path is the easy path, you don’t need to argue people onto it.

Closing thoughts

A landing zone is not a diagram or a toolkit, it’s a system of work. When you treat it like a product, the safe path becomes the easy path: teams start on paved ground, guardrails run in the path, and the proof that change is safe travels with the code. The result isn’t abstract “governance”; it’s faster lead time, fewer surprises, and a platform people trust without asking permission.

You don’t need to boil the ocean to get there. Ship the minimum viable landing zone, measure outcomes (lead time, CFR, MTTR, conformance), and evolve by versioned upgrades rather than new committees. Keep the base thin: identity, isolation, encryption, telemetry, tagging, and layer capabilities where they’re justified. If a control doesn’t lower risk or speed recovery, it’s latency; delete it or move it into the pipeline.

If you do one thing after reading this, make it this: pick one service, put it on the paved road, and prove it end to end: bootstrap, deploy with a canary, emit evidence, and practice rollback. That single flow will tell you where to tune next and, more importantly, it will show your organisation what “guardrails, not gatekeepers” feels like in practice.